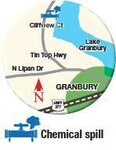

All Jacob and Ashley Price want to do is move out of their house on Cliffview Court just north of Thorp Spring on Tin Top Highway.

“We didn’t feel like that up until not that long ago,” Ashley said.

But the Prices and their four kids are stuck.

Along with Brenda and Mitch Raybion and David and Lesa Kimbrow, they are parties to a lawsuit against NextEra Energy and Eagleridge Operating, who own and operate the Thomas Unit North Facility, a natural gas well that the plaintiffs claim spewed contaminants that are still flowing into their property.

The plaintiffs say they don’t feel safe drinking their water. And according to the Hood County Appraisal District, the values of the Price and Raybion homes have dropped from over $200,000 to zero.

In July of 2017, a pipe under the well broke, and a substance called produced water, which is a byproduct of natural gas drilling, began leaking into the ground.

That water contains chlorides and other contaminants, including harmful chemicals like acetone and cancer-causing benzene. The closest areas to the well had over 600 times the legal limit of chlorides in runoff water.

But according to the lawsuit, filed by Austin-based attorneys Mark Guerrero and Mary Whittle, Eagleridge continued to operate the facility for 74 days after the leak began. The Raybions and the Prices say they were never notified of the severity of the spill, and had to find out through their neighbors.

“The Raybions came to my door,” Ashley said, “and they were like, ‘Hey, do you know about this oil spill?”’

“I was like, ‘I’m sorry, what?’”

Eagleridge and NextEra had settled with the owners of three properties affected by the spill, in part by purchasing the properties. But the Prices, the Raybions and the Kimbrows didn’t receive anything.

The Kimbrows owned and operated the Warriors for Christ Church, which ministered to prisoners and drew crowds of nearly 100 people on Sundays. That church, which sits on the same property as the well, is no longer safe, David Kimbrow said. It shut down last year.

And the chemicals have not dissipated. The companies built a trench on one of the now-abandoned properties they purchased, attempting to collect the contaminated groundwater. But benzene was recorded in a report to the Texas Railroad Commission in January 2019, and chloride continues to migrate downhill and through the limestone bedrock.

NextEra declined comment through a spokesperson. Eagleridge did not return a request for comment.

‘WORTHLESS’

The Prices have four children, all under the age of 15. They were close to selling their house in 2017, and were preparing to move to property in Weatherford.

But that all changed.

“Our kids were prepped for that, our lives were prepped for that, everything was going that way,” Ashley said. “Our whole life has been completely changed, and (the companies) just absolutely do not care.”

Jacob Price bought his first house at the age of 23. He’s spent his entire adult life improving every property he’s bought since and building toward something better for his family.

“I have a house valued at $315,000 that I’ve been working towards, gathering that since I was 23 years old,” he said. “And now an oil company comes in and makes it worth zero.

“And I have spent every spare moment of my life building that. It was all for nothing. I’m sitting here on 15 years’ worth of work that is worthless.”

It’s not just a financial toll on the Prices. Their kids weren’t allowed to play outside for fear of contaminants. And in January of 2019, just when they had felt comfortable enough to become “lax” and let their kids outside, the report of benzene came in.

“It’s overwhelming,” Ashley said. “I kinda started feeling like I was stupid for worrying for that long.

“My kids are worried because they don’t want to be here anymore. We don’t let their friends come over and play. We stopped having small groups at our house for our church.

“It’s not like it’s worthless, and we can still stay here. It’s worthless, and it’s not safe.”

The Prices are afraid to drink their tap water. The companies have provided bottled water for them and the Raybions.

“That is the only concession that they have made for us,” Jacob said. “Which is an admission of guilt, but it’s kind of like pissing on a brush fire.”

NO MORE REUNIONS

The Raybions have lived at their home on Cliffview Court for over a decade. They were here before the facility was built.

Mitch Raybion works in cranes and heavy lifts for oil refineries, and has spent much of the last two years on the road working in Houston. He recently earned a promotion that means he will work full time in Houston, leaving his wife Brenda alone in their house on contaminated ground.

“This was not what we bought into,” Brenda said. “We were preparing our property to be sold.

“I’m supposed to be with (Mitch). We were preparing to go on the market. But the hazard barrels came at the bottom of the driveway, they parked their equipment there, and it was just overrun by aliens, it seemed.”

Brenda has worked tirelessly to improve her home’s value, doing everything from landscaping to repainting to installing hardwood floors. In the meantime, the Raybions have welcomed their seven children and 17 grandchildren for holidays and reunions.

“We bought this place as a gathering place for all of our kids and grandkids,” Mitch said. “A place we could be proud of.”

The pond in front of their house was of special importance. Their grandkids learned to fish there. Mitch was baptized in it. Now the Raybions won’t let anyone near it.

“We don’t really have family gatherings anymore,” Mitch said.

A line of oak trees near the pond died just after the leak began in 2017. Rust-orange water, a possible indication that chlorides are still present in the soil, seeps through the ground on their property and runs into the pond.

But according to the lawsuit, Eagleridge and NextEra have refused to conduct sample tests on the Raybion property. The plaintiffs say it’s because the companies are afraid of what they might find.

In the meantime, the Raybion home is worthless, according to the appraisal district. And the people in it have lost a sense of security.

“It wasn’t a lot, but it was a lot for us,” Mitch said. “It ain’t the Taj Mahal, but it’s home.”

A HARD FIGHT

A court date has been set for September in Hood County. But winning legal battles against oil companies, especially in Texas, can be tough.

Professor William Keffer, who specializes in oil field pollution cases and is the Janet Scivally and David Copeland Endowed Professor of Energy Law at the Texas Tech School of Law, said plaintiffs have a harder job than defendants in these cases.

“Frankly, it’s difficult,” he said. “You basically have to explain away all other potential explanations for your contaminants in your water supply. Leave the one explanation as the only possible explanation.

“It’s a big bar to clear.”

The levels of contaminants also make a difference, Keffer said.

“Our technology has allowed us to measure contaminants at very minute levels,” he said. “Just because it’s measurable doesn’t mean it’s hazardous.”

The plaintiffs are petitioning for three main goals, according to attorneys Guerrero and White. They want the companies to be ordered to clean up the area to “a standard that befits a neighborhood.” They want compensation for their loss of property value and damages paid for the “mental anguish” they’ve experienced.

And perhaps most crucially, they want the liability regarding the contamination on the properties to rest with the companies. Otherwise, the plaintiffs can be held accountable if they sell their property and contamination persists under the next owner.

Ashley Price put it succinctly.

“I want us to be able to move,” she said. “Obviously this is not going to be getting better any time soon.

“They act like it’s going to be over in a couple of years. We’ve already been going with this for over 12 months now, and it’s getting worse, not better.

“We just want to get out.”

grant@hcnews.com | 817-573-7066, ext. 254