From the U.S. Army Air Forces station Thorpe Abbotts in England, retired Master Sgt. Dewey R. Christopher used his mechanical skills to keep the Army Air Forces bombers in the sky during World War II.

Now 96 and living in Gran-bury, Christopher returned to England this summer for a special tribute.

A building was named in his honor at Royal Air Force Mildenhall in England.

“It’s a great honor,” Christopher said of the tribute. “I was overjoyed when I learned the news.”

Various streets and meeting rooms bear the names of officers and members of the flight crews. But for the Dewey R. Christopher Professional Development Center on the base, it was suggested that an enlisted member from the ground group be honored.

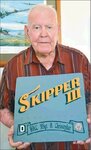

Christopher was given the royal treatment at the ceremony June 21. A KC-135 was fitted with a metal plate bearing the name Skipper, along with the Square-D tail marking. It provided a backdrop at the ceremony.

Skipper was the name of a B-17 bomber under Christopher’s care. The aircraft’s pilot dubbed the plane Skipper, a nickname that he called his wife.

The tail markings identified which unit an aircraft was assigned. When bomb groups joined massive formations before heading toward their targets, the tail markings helped members of the same group form together.

The Square-D marking designated the 100th Bomb Group and it is the only World War II tail marking still in use today.

MECHANICAL APTITUDE

Christopher grew up across the Red River from Wichita Falls in Oklahoma.

“I graduated from high school in 1941, and there weren’t a lot jobs available. The military was the best job out there,” Christopher recalled.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, Christopher enlisted Dec. 12, 1941.

On his first try, Christopher was not admitted due to vision problems. He went home, got glasses and was able to pass the physical.

“All of the boys coming in off the farms had a pretty good mechanical aptitude, that’s how we got in aircraft maintenance,” Christopher said.

His training took him coast to coast and points in between, including time at the Boeing plant in Washington.

“We were able to see how the plane was put together. It was the best training we had,” Christopher said.

Following various stops for crew chief training, Christopher landed in Kearney, Nebraska.

“They had the planes there,” Christopher said of Kearney.

SHIPPING OUT

In May 1943 he was shipped out to East Anglia, England, as a crew chief for the B-17.

Each crew chief had their own hardstand to work from. The hardstand was essentially a concrete pad where the planes were parked. Many hardstands also had a tent or a small shack for supplies.

“It’s where we worked on the planes to get them ready to fly

again,” Christopher said.

“Dad pretty much lived on that hardstand. If he had any down time, he could go to a Quonset hut across the airfield and take a shower,” son Gary Christopher said.

FIRST MISSION

It was a proud moment, Christopher said, when his plane flew its first mission on a bombing run. Targets in Germany and France included airfields, industries and missile sites.

The bombers would fly in close formation with an escort by fighter planes. Early in the war, the fighters only had the fuel range to take them to the coast of Holland - after that the bombers would be chewed up by German fighters and antiaircraft fire.

There were times that 1,000 big engine bombers were in the sky at one time. Between the heavy fog and the number of planes in the air, collisions occurred between our own planes.

“The fog was so thick over there,” Christopher said. “It was like nothing I’ve ever seen.”

Recalling a particular run to Munster, Germany, Christopher said, “We waited and waited for our planes to return. We finally learned that all of our planes were lost. We had 12 planes shot down and lost 121 men that day.”

After about two years in England, Christopher was shipped back to the states on the Queen Mary.

Following his military service, Christopher was a mechanic with American Airlines for 41 years.

These days, he enjoys reunions with the 100th Bomb Group every other year and a mini-reunion each year in Palm Springs. “There’s only a few of us left,” he said. “Now the sons and daughters are keeping the group alive.”

Christopher and his son are active with the 100th Bomb Group Foundation.

“It’s the mission of the Foundation to keep the history alive,” Christopher said. “We want people to understand that freedom is not free.”

While in England, for the naming ceremony in June, Christopher and his son went to Thorpe Abbotts, where he was stationed during WWII.

“He spent his 20th and 21st birthdays there, and then turned 96 while we were there visiting,” Gary said of his dad.

The trip in June was Christopher’s fourth time back to England. He also traveled across the pond in 1986, 2012 and 2017.

dschneider@hcnews.com | 817-573-7066, ext. 255

‘We want people to understand that freedom is not free.’